President Donald J Trump. While the controversial and divisive topic is almost too easy to mock, the reality is that the Trump administration is making some genuinely questionable, if not downright irresponsible attempts at policy making that could send the U.S. automotive industry, and indeed the world, backwards.

At a January meeting with executives of the U.S.’s largest manufacturers like Fiat Chrysler, GM and Ford, there was an emphasis placed on reinvigorating the American manufacturing scene. The outsourcing of production to Mexico in particular was, in Trump’s most eloquent of phrasing: “Happening… happening, bigly.” Trump made his feelings known via public attacks at the manufacturers via Twitter ahead of the meeting.

Now, we’ve seen Trump’s first 100 days in office play out, and witnessed his automotive focal point pivot instead toward the removal of the industry’s “burdensome regulations”. It may well have turned out that erratic 3am tweets threatening to impose 35 per cent tariffs on American-badged imports from Mexico weren’t the easiest policies to actually execute in office, so, he instead put the environment down the barrel of his sights.

It’s politics after all, so how will president Trump provide the American people with the jobs, jobs, JOBS that he tirelessly campaigned on? Well, according to the White House’s ‘America First Energy Plan’; “President Trump is committed to eliminating harmful and unnecessary policies such as the Climate Action Plan.” The elimination of Barack Obama’s C.A.P would result in, according to the White House: “Increasing wages by more than $30 billion over the next seven years.”

Trump stands by his business-first, environment-second stance, telling Fox News Sunday: “We’ll be fine with the environment… We can leave a little bit, but you can’t destroy businesses.” This sentiment materialised on the March 28, when Trump signed an executive order that called for the immediate review of America’s current means of energy production and regulations, in particular, the recently implemented ‘Climate Action Plan’. The order can only be described as an attempt to swipe all of former president Obama’s regulations, targets and incentives for renewables firmly off the table.

Interestingly enough, president Obama pulled a similar move when he took office from George W Bush in 2008. However, the changes implemented were aimed at improvement, rather than going back to the stone ages. CEO of the World Resources Institute Andrew Steer described the move as; “taking a sledgehammer to U.S. climate action.”

The man who has spent years calling for these changes is ironically now the head of the EPA – America’s Environmental Protection Agency – a man named Scott Pruitt. The Washington Post says that: “Pruitt has spent much of his energy as attorney general fighting the very agency he is being nominated to lead,” and now leads it, with a somewhat iron fist in regard to the environment, as Senator Edward J. Markey characterised: “Pruitt would have EPA stand for Every Polluter’s Ally.”

Hardly the man you’d want in charge of an objective Environmental Protection Agency. Trump’s executive order is little more than barely disguised nepotism, under the veil of a campaign promise for jobs. After all, his Secretary of State Rex Tillerson was up until last year the CEO of ExxonMobil. The order may well have the influence to wind-back the clock to the good ol’ days of the U.S. auto manufacturing scene; the days filled with 6.0-litre minivans and what at times seemed to be a competition of whom could produce the thirstiest car on the road. The underlying problem is that these days ushered little but financial ruin for the manufacturers, when consumers began taking things like fuel consumption more seriously.

The most recent move from Pruitt as chief of the agency was to remove half of its scientific board, in favour of ‘industry-aligned replacements’. Members of this board previously made up healthy amount of academics, who now stand to be replaced by representatives from the same industries that the EPA is attempting to regulate. Deborah Swackhamer, chair of the board, told the Guardian that “the committee has been eviscerated.”

“We assumed these people would be renewed and there was no reason or indication they wouldn’t be. These people aren’t Obama appointees, they are scientific appointees. To have a political decision to get rid of them was a shock.”

So, why all the American political context? If Trump’s removal of Obama’s Climate Action Plan sends a message to America’s big three manufacturers that thirsty, large capacity engines are back on the menu, we could witness the downfall, rather than expansion of an automotive industry that has been performing strongly post-bailout.

Trump, speaking in Michigan in March, told autoworkers: “The assault on the American auto industry, believe me, is over. Under this system, we will reduce burdens on our companies and on our businesses. But, in exchange, companies must hire and grow in America.”

Trump’s new plan seems to completely disregard the fact the feds came to the saviour of General Motors and Chrysler with an $80 billion bailout; Ford got a slice of the pie too because it felt it was an unfair advantage for the competition. The government in return demanded they sharpen their pencils and start designing products for the future, not yesterday.

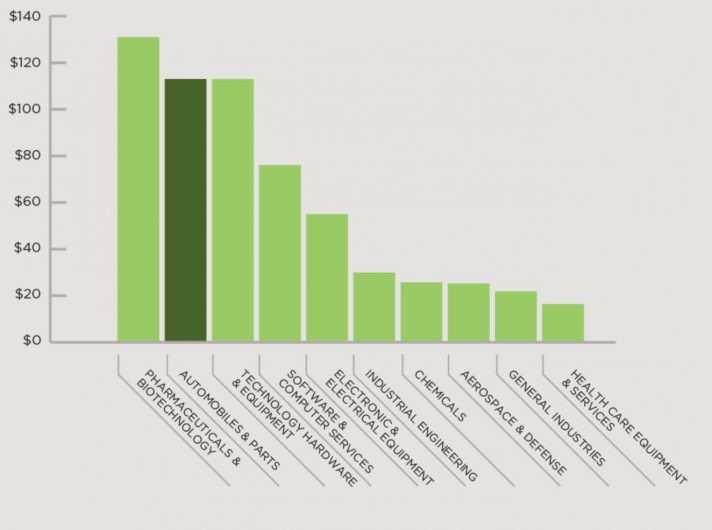

Taking a look at the statistics, they did exactly that. According to the American Automotive Council: “In 2013 and 2014, manufacturers accounted for roughly 75 per cent of the growth in the U.S. R&D,” and in addition, R&D increased 55 per cent from 2003 to 2013. During nearly half of this time, the manufacturers were embroiled by financial woes and forced to invest in R&D. In terms and conditions of Obama’s bailout was an assurance that the ‘Big Three’ would meet a 35mpg (6.7L/100km) fuel efficiency standard by the year 2020, and a 54.5mpg (4.3L/100km) rating by 2025.

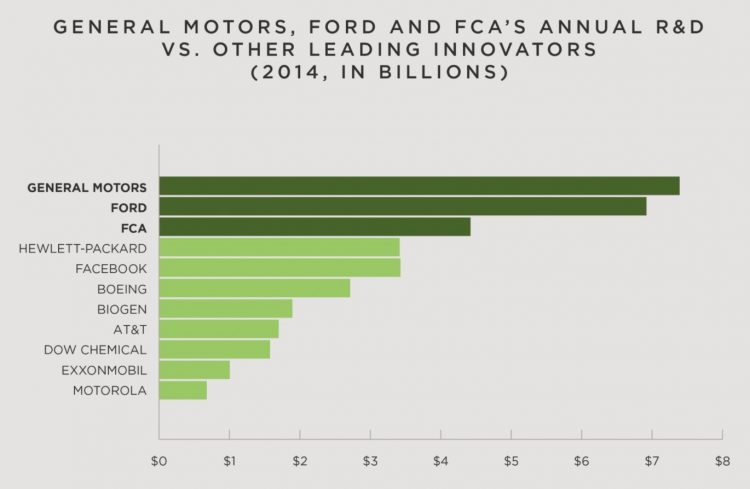

Competition from domestic and foreign marques alike in the realm of new technologies as well as the bailout were the catalyst for U.S. manufacturers to start taking alternative drive systems seriously, and match it with an investment into the research and development of such systems. The elephant in this figurative room is that if, and only if, Ford, GM and FCA revert to bad habits, the American auto scene could ironically be undermined by the ‘America First Energy Plan’. This could ultimately see America slide to the back of the line in terms of automotive innovation.

A possibly disastrous scenario is that the manufacturers suddenly become lax to environmental concerns, and in turn slash R&D budgets in the absence of pressure from a federally-enforced ultimatum. There would be less, indeed no incentive to create new technologies, all the while operating under a system that is trying to rid itself of ‘burdensome’ environmental standards.

The American auto scene can’t afford to let its rivals push ahead while they maintain a state of ignorant bliss. If Trump expects jobs to materialise, he’d better hope that the brain’s trust at GM, FCA and Ford do the exact opposite, and don’t get complacent with lax environmental laws. After all, FCA, Ford and GM together employ 45,000 workers at their R&D facilities, according to the AAC, so it would prove nothing more than detrimental to all parties involved if research and development budgets take a hit.

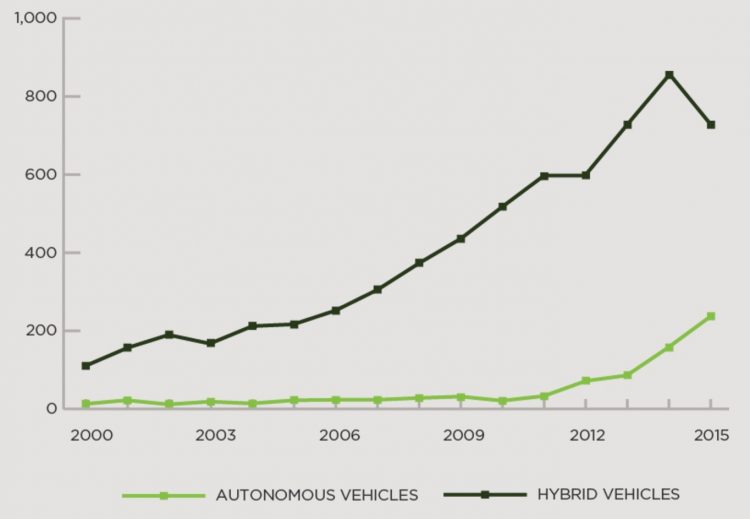

How the future will play out is largely in the hands of the buying public, and how the executives high up in the food chain direct their future-thinkers employed at R&D departments. Hopefully they’ll recognise that public interest and money is slowly but surely moving in the direction of a more environmentally sustainable automotive sector – particularly in the area of EVs. Look no further than Tesla’s soon to be released Model 3, which received 400,000 pre-orders as of one year ago. Also, while the executives at GM, Ford and Chrysler weren’t exactly hasty in their response, the writing was on the wall for gas-guzzlers; U.S. market share had declined from 70 per cent in 1998 to just 53 per cent in 2008… The priorities, and in turn buying habits of the American populous had moved onto more 21st century ideals, and executives in 2017 are obviously aware of this after the government had to save their businesses from the brink of oblivion.

It’s also worth noting that big manufacturers plan their products many, many years ahead of time, so while policy may take dramatic turn, the products planned for the coming years may have been influenced very little, or not at all by Trump’s executive order. An indication of things to come will be analysing the amount of capital invested in R&D by the big three, particularly in the realm of new technologies. It now remains in the hands of the big three’s commitment divestment from old-school technologies; unfortunately, this is something only complicated by changes to environmental standards, and falling oil prices.

In conclusion, it’s worth mentioning that the purpose of this piece isn’t to shame the internal combustion engine. Far from, actually. While it may on the surface appear hypocritical to promote awareness of climate change policy on a site that more often than not celebrates high-capacity, high-power engines, you cannot ignore our industry’s evolution. Darwin’s concept of survival of the fittest very much proved that there is little place in this world for the mass production of high capacity engines powering SUVs and minivans for school runs; declining vehicle sales only proved this. Instead, our industry is in a state of flux and evolution to make mass transit vehicles less detrimental to the environment, while maintaining a healthy selection of performance cars as more or less a special pleasure for those of us who worship the found of a fire-breathing V8.